“Listen to that,” says Neil Gregory as he pushes the side doors of the Husky seaplane open. A blast of cold Scottish air rushes in. I hear nothing but the chinking of the engine cooling and the light rain on the roof. I look out the right window and down at the float on the glimmering darkness of Loch Earn. Raindrops make ringlets on the water and the Husky aircraft bobs back and forth. I can see cars driving along the shoreline, their drivers wondering what the hell a plane is doing out on the Loch on this gloomy Monday evening in June.

I wait for Neil to say something, half wondering if he’s about to come out with another nugget of flying wisdom. But instead, his head kinks round from the front seat and I see his infectious wide-grinned smile. I start laughing. So does he. Neil knows I’m already hooked.

“This is the beauty of seaplane flying,” he says with pure happiness in his voice. “So now I could step out onto the float, take in the fresh air, do some fishing, maybe even have a pee,” he adds with that same smile again. “Be careful not to fall in if you’re having a piss though!”

I find myself picturing the floatplane scene in Indiana Jones where the pilot is sat on the float, fishing, only to jump up in panic as he sees 100 men with bows and arrows chasing after Indy. My daydream is cut short as Neil closes the bottom and top parts of the Husky’s doors. He starts up the engine, ruining the silence, taxis us over the water into wind, spray splashing up from the floats and then launches us back up into the sky.

NEIL’S SEAPLANES

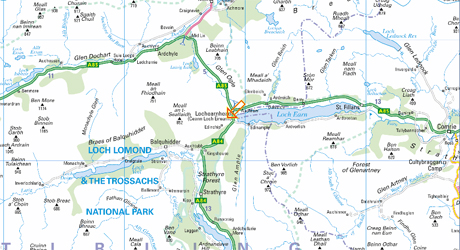

I arrived at Loch Earn in the late afternoon on a Monday. Neil wanted to take me flying straight away. I’d spent the day travelling up here to his watersports centre at the eastern end of Loch Earn. After a BMI flight from Heathrow to Glasgow and an hours drive north in a hire car, I spent the afternoon in his cafe, drinking tea served from a proper tea pot and finding out a bit more about the intricacies of seaplane flying. I wanted to learn more about the types of pilots who come up here too.

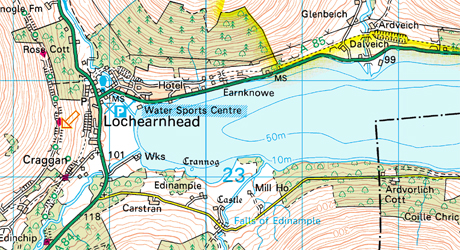

Neil Gregory owns and runs the watersports centre you see on the map here.

We’re chatting because the good old Scottish weather is keeping us grounded. But Neil, as you’ll soon find out, has unlimitless optimism, and remains hopeful that we’ll fly later that evening. From his cafe you can see his gorgeous red Aviat Husky seaplane parked amongst the rest of the boats and the pine trees. It’s the last thing you’d expect to see at a boatyard. I find it incredible that he’s not had it vandalised.

The entrance to Neil’s watersports centre, cafe and car park where he keeps his Husky.

Neil’s Husky looks cold in the boatyard of the watersports centre. This was the weather when I arrived on the Monday afternoon. It was June! Looks more like January.

Loch Earn itself is just 1.2km at its widest point but it’s very long – 10.5km in length – and it’s straight too so almost has a runway feel about it already. Steep-banked hills surround the shorelines. I couldn’t help but look at the grey cloud and mist rolling over them right now. It was looking more and more likely that we wouldn’t be flying today. Neil suggested we learn how to pre-flight a seaplane instead.

As we’re doing the walkaround, I ask Neil how he learnt to fly. He started out by flying gliders. “I think flying aerobatics in a glider is actually better than in a powered aircraft,” he says. “People try and make flying too complicated. You can sum up how to fly an aeroplane in one phrase and that’s energy management.”

Turns out energy management is just as important when you’re taxiing over the water on floats. It comes down to hydrostatics. Neil announces that the floats look like a ‘Wallace & Grommet’ creation. I laugh. You can see all the rivets. “Anyone with a vaguest understanding of anything can see how these floats are put together,” says Neil as he tightens up a loose nut on a panel of Husky’s fuselage with a multitool. “It’s grown up Meccano.”

While the floats are well-built, they still take in water, so one of the pre-flight checks is to use a hand pump to suck out the water in each section of the float. There’s a plug you pull out in each section. I have a go and derive childlike pleasure in whacking the pump up and down and hearing the squelch noise. One day I’ll grow up.

I step up onto the left hand float for the first time. I’m soon distracted by all the bracing wires they have running to the fuselage. I’m then drawn to the control cables running from the underside of the cockpit to tiny rudders on the back of the floats; they must be connected to the rudder pedals, I think to myself. The floats on Neil’s Husky also have wheels to make it an amphibian, so it can land on hard runways as well as water. It’s the ultimate flexibility. Should the donkey stop while you’re in flight, you now have two choices of where you can land; either on land or on water. Even if the wheels don’t come down, you can still put a floatplane down on hard ground in an emergency – they act as shock absorbers. “It’s certainly my choice of plane for having an engine failure in,” Neil adds as he walks around the plane, removing wooden chocks. I follow him on his walkround. Next, he grabs a wooden paddle from the cabin. A paddle is essential equipment on a seaplane, and has helped god knows how many pilots get themselves out of the shit. It also has a secondary use. Neil uses it to remove the pitot tube cover from the leading edge of the wing because it’s up so high due to the floats.

I’m staring at the sky, wishing for better weather, but Neil is looking at the water on the loch. I suddenly realise it’s not so much the cloudbase and the light rain that’s stopping us from flying. It’s actually the choppiness of the water. I’m still thinking as a dry-land pilot when I really need to be thinking more like a sailor. “As well as airmanship, there’s a whole aspect of seamanship that comes into it,” he says as he points out the wave height and how the wind is now finally starting to run directly down the length of the loch instead of across it. I can’t help but feel like I don’t know what I’m supposed to be looking at with these waves. Knowing when the water conditions are ok to fly from is only going to come from more experience.

Neil hands me a lifejacket. I jump up into the Husky’s rear seat. Registered as G-WATR (water, geddit?) inside it’s warm and cosy. A retreat from the wind and light rain outside. It’s early evening and Neil could have easily called it a day, but I’m soon to find out that Neil is anything but your typical instructor.

He jumps in the front, a seasoned expert, pulls the upper and lower doors together. I marvel at the view over his shoulder. Usually you see an airfield but being here in parking area for boats just metres from the edge of a loch feels bizarre. A tree branch is draping its leaves on the right wing, which I’m worried about, but Neil isn’t and he starts up the 180hp engine to let it warm up. The rain drops on the windscreen rush rearwards in the slipstream from the propeller and Neil’s reassuring voice comes into my headset.

“You ready then Dan?”

“Absolutely,” I say.

Neil puts on the power. We’re taxiing using the wheels. He kicks it round to face the water and I’m beside myself with excitement. We’re not going on the water are we? In a plane. Doesn’t seem right. The floats put your viewpoint up higher than in other light aircraft. What we’re doing now, taxiing an aircraft into the water, would usually mean the pilot had got things really wrong. Some tourists and some fishermen have heard the noise and come to watch us. From inside the cockpit it feels wrong to be dipping our toes into the water. Neil gives some extra throttle and we’re fully on to the water and I realise we’re floating. It’s just like being in a boat, except I’m in a plane. Being sat in a cockpit with the sensation of being on a boat feels weird. For me, it felt like wearing Wellington Boots and stepping into a stream for the first time; you can see you’re in water, and you can feel the pressure of it against your feet, but your feet aren’t getting wet. It seems obvious that the plane would feel like a boat, but I really hadn’t expected the sensation to be so strong.

On the water in G-WATR for the first time.

Meanwhile, Neil is busy working the throttle in small bursts and using the rudders to steer the Husky around the anchored boats. He’s pulled the wheels up into the floats.

It looks narrow between the parked boats, two in particular, which I think we’re going to hit, but he steers us round them with literally inches of wingtip clearance.

“That was pretty tight huh?” says Neil as he backtracks us down the loch to our take off point. “The hardest part of seaplane flying is handling the aircraft on the water,” he says. “It’s about feeling what the wind is doing. It blows you just like a yacht. We don’t have brakes on this so you can’t just stop, you have to used the weathercock effect on the tailplane and the propeller slipstream to help you get where you want to go. Think like a sailor.”

I feel overwhelmed by two things; the amount of information Neil’s giving me and the sailing sensation. But both are making me want to learn more about the intricacies of it all. I tell Neil this and he says that happens to every pilot that comes up to fly with him.

“Unlike a conventional aeroplane, with a seaplane you’ve got a huge number of variables against you all the time, trying to cock you up!” he says bluntly with his trademark smirk.

Neil makes every single item of his pre-flight check count. No lip service here to his checks, he properly follows the list. I notice he pays a lot of attention to make sure the wheels are retracted in the floats – and there’s a mirror down on the float which he looks down at to confirm that the wheels truly are stowed away. Taking off with the wheels hanging out of the floats will flip us into the water. I check that my straps are tight and then look over his left shoulder at the expanse of the loch.

“Ready,” he says.

“Yep, ready,” I reply.

The view over Neil’s shoulder just before he applies power to take-off.

The engine roars, we splash forward, picking up speed while bobbing up and down. I feel heavy bumps into my seat as the floats hit the waves, just like the feeling you get when you ride a jet ski. The time between the bumps gets shorter as we skim along faster until there’s a noticable crescendo of bumps and then silence. We’re airborne. Neil deliberately keeps her low (more about why he does later) and its utterly exhilarating. The Husky accelerates fast, much much faster than the Piper Cub I fly back home. Neil rolls her over to the right filling my view out of the window with dark water and inducing a mild panic in me at just how close the wingtip seems to the surface. But Neil knows this little plane by inches and he then rolls level and pulls the Husky’s nose up high, and we zoom climb up to 1000ft and we’re overhead the southern shoreline. We’ve got views of Scotland at its plushest green.

The white building is an old castle.

“Wow! I can’t belive how much more power this has than a Cub,” I say.

“It’s a 180hp engine with a constant speed propeller so it’s got some poke,” says Neil. “Here, look down at that castle.”

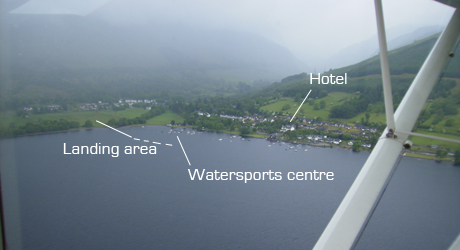

We circle overhead and then fly back towards the watersports centre. I see it with all the tiny boats moored up. I start to get a feel for the local area. We then fly right over the top of Lochearnhead village and the hotel I’m staying in. We’re low, about 500ft agl, with hillsides close on our left and the loch on our right. I feel like I could put my hand out of the window and touch the pine trees.

Hills and pine trees to our left.

View over Neil’s shoulder as we fly down Loch Earn, late on a Monday afternoon in June.

We don’t speak as we fly down to the western end of the loch hoping to see calmer surface conditions there so I can start having a go at flying some circuits and make my first ever landing onto water. I can see cars below snaking along the shore road below, tradesmen in vans heading home for dinner and tourists on their way back to their B&Bs.

Neil talks me through a circuit as he flies one. His instructor patter is pitched perfectly. I try and remember everything he’s saying so I can fly the next one. We fly a final, the loch filling up the forward view and he flies the Husky down over the water until the floats touch. We skim and then slow down extremely quickly. In seconds we change from a flying sensation to a floating one. Neil pulls the mixture to cut-off and we sit peacefully for a few moments to take it in. We’re now where this feature started off.

WATER WINGS

“You have control Dan,” says Neil as we’re on the climb out after our first landing. “Keep us climbing up, 75kts, yep that’s good. I want you to turn crosswind to the left and then level us off at 1000ft.

“I have control,” I reply, loving the feel of the Husky in my hands for the first time. I turn crosswind which has me heading straight towards the hillside. I’m not used to seeing the front windscreen filled with a view of green and it makes it hard to judge your distance. Although the hillside looks close, I actually have a lot more distance to play with than I think.

Neil tells me to acclerate to 120kts and then bring the throttle back to cruise. The Husky is really easy to trim and hold an attitude. They say the Husky was designed with the best features of the Cub in mind, only better. They’re not wrong.

We do our pre-landing checks, turn base leg, set up the descent and then turn final. Everything is the same as a normal aircraft, but the thing worrying me is knowing when I need to flare above the water. Pilots reading this who are currently learning to fly and land on grass or tarmac can appreciate this sentiment, so how different would it be to land on water? Not that much different actually. You’re slightly higher up due to the floats, so you have to flare a bit earlier than you think. The picture out the front for the flare is slightly nose higher than normal too. A further worry was what happens when you put the floats on the water. What if I touched down right on the tips of the floats? Or what if I touch down on one float first? Then there was the fundamental question of what does it actually ‘feel’ like to land on water? I’ve given this much thought since my visit to Neil’s Seaplanes and the best way I can describe it. When those floats touch the water, it kind of feels like sitting on a sledge and skidding along on snow. You can feel there is friction below you, something rubbing. It also reminded me of sitting on a skateboard and sitting back on the tail letting it rub into the road to slow down.

I was pretty nervous but I made a half decent landing on my first attempt. Re-taking off felt the same as when Neil had done it except he told me more about the ‘step’. This is when the floats reach a certain speed when they lift up out of the water. The visual attitude out over the nose changes so you have to be ready for it and recognise what it is and when it happens. I was really surprised by just how little back pressure I needed to rotate. It isn’t really a rotation at all. The Husky flies itself off. Earlier I said that Neil keeps her nose low just after take-off. Well, the reason for this is that after you get airborne those huge floats coming out of the water and into the air create a load of drag, so you have to be aerodynamically sensitive and keep the nose attitude low while the Husky overcomes that drag and builds up flying speed.

I flew a further three circuits, each time I loved the feeling of landing and taking off from the water. Neil then took over to demonstrate just what else can be done in a seaplane. Unlike a tarmac runway which has a fixed direction, a seaplane pilot can use any direction across a body of water to take off and land directly into wind. But would you believe you can also take-off in a curved arc too? It’s a useful technique for where there might not be a long lake to get airborne from. I didn’t quite believe Neil that you can do this until he showed me. And to prove the point he played about skimming the Husky on the loch, tipping from one float to another by roling the control stick left and right and using the rudder pedals. We went round in circles on Loch Earn. Everytime he flew on one float, the Husky leant right over and I swear at times, the view out the back of the plane and down at the wingtips made me wonder if he was going to put the wing in the water.

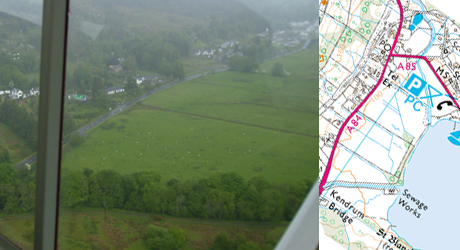

The home-end of the loch was starting to look gloomier so it was time to fly back. I kept control and followed the northern shoreline home and then crossed over the Loch to the southern shoreline to position on a downwind leg (see images below).

Downwind.

Neil took control at the end of the downwind leg. He turned right, then showed his competency even further by sideslipping down over a grassy field just before the loch and then flying between a gap in the hedge to pass over the gravel shoreline and fly a short-field landing so we had less distance to taxi back into the watersports centre.

SEAPLANE TRAINING

In the bar of the Lochearnhead Hotel that evening, we stand and drink lager with panoramic views of the loch. The hotel is run by Robert and Amanda and the pair are used to accomodating pilots who have come up to fly with Neil as it’s just a two minute walk away from Neil’s watersports centre. The bar is also Neil’s local boozer. The hotel’s a bit of a resource for the village and other residents are comfortable enough to come and ask Rob and Amanda for a mug of sugar or milk if they’ve ran out. As Rob puts it, “This hotel is the heartbeat of the whole village.”

Neil agrees, saying the hotel punches well above its weight. As we drink I ask him a bit about what reasons people give for wanting to come up here and fly a seaplane. “I have plenty of people interested. It’s a holistic approach to flying training. When someone comes up here I make sure that they’re not treated like a number. Anybody who has gone to the effort of travelling up all this way to Scotland wants to learn. Their expectations have to be managed, but they come here knowing that.”

I can’t help but feel that Neil is alluding to the weather and the fact you might find yourself sitting around waiting for the weather. Then as if he’s read my mind, he says, “Flying is part of the reason people come here, but of course there are all the other things you can do up here like walking and climbing. Some even come up here simply to de-stress from work.”

One such pilot is Chris, who has 300 hours as a PPL(A) holder. He did a full seaplane conversion course last summer and has returned this week not only to fly the Husky and keep current, but to also unwind from his hectic job as a consultant. Chris originally learnt to fly at Blackpool, then flew with a club at Denham and now flies from Fairoaks with the London Transport Flying Club.

“I find this community up here so welcoming,” he tells me after speding the day driving up from Colchester. “Last year when I flew here I took some of the best photographs I’ve ever taken,” he enthuses. “I’m no photographer but I’ve got some great flying shots. People say they look amazing.”

It took Chris 12 hours of flying in the Husky before he felt completely comfortable operating from the water. “I had difficulty taxiing on water and those 12 hours in a Husky are considerably different to 12 hours in a Piper Arrow. I soon learnt that you have to be a proper Captain and it’s you making the decisions. You learn so many things you’ve never even thought of before. I’d now like to get to the stage where I can jump in a seaplane, go places, land and camp overnight. Maybe do some loch-hopping too.”

Chris made contact with Neil after seeing his website. Don’t bother emailing Neil; he doesn’t use email. Instead he only lists his phone number on the site as he prefers to speak to pilots on the phone so he can have a proper conversation about it instead of a written exchange. If only more businesses out there would do this eh? Talking on the phone also helps Neil establish exactly what somebody wants to get out of their seaplane flying.

“I’m very keen that people do not see this as just getting a tick in the box,” he says. “The first thing I ask is why do they want to fly a seaplane. Are they going to buy one? Do they want to work as a seaplane pilot? Then depending on their answer I can suggest whether it’s best they start with a taster flight first, instead of booking up a whole course straight away. If you’re going to do the full course, then it requires a lot of discipline and full attention to fully learn the finer points of seaplane operation.”

Seaplane training isn’t just differences training, there’s an SEP seaplane class all of its own. Bear this in mind on your licence. However, PPL(A) SEP holders can fly with Neil to do a bi-ennial flight review which is required to revalidate your PPL.

“I would actively encourage any pilot to try a seaplane. Sadly most PPLs are woefully underchallenged. The thing I observe most is poor spatial awareness and a poor common sense. I think a lot of people in flying have tried to proceduralise common sense but when you do that you lose the bigger picture. I’m lucky in that I tend to think of things in pictures.”

I realise as I drink my pint that not only I am learning about seaplanes but I’m also learning about airmanship and how another pilot sees the world. At this point I wonder how Neil became so passionate about flying, so I ask him.

“When I was a kid I used to look up at seagulls and just wish I could fly,” he says. “There was a particular hill, with a perfect view, and I used to stand on that with my anorak open and I suppose you could say I dreamed about flying myself off it. You know, it’s impossible to fly with a plastic mac though,” he laughs.” Neil came to Loch Earn 15 years ago and started running the cafe and watersports centre for a steady income and then instructed as and when. He loves that it’s unusual and rare. There are just four seaplanes in Scotland, three in England and one or two in Ireland. It’s a shame because during WWII, seaplanes were used extensively all over Britain. England banned them from landing on lakes after the war. Now only Scotland and Ireland allow them. Even France has banned seaplanes from landing on lakes. Neil opens up that he has had a real battle to keep his operation going. He’s had arson attacks on his facilities, wranglings with the CAA over converting a standard Husky into a seaplane and all sorts of local politics and backstabbing. “I guess doing this has been a monumental struggle requiring faith and enthusiasm in the face of bureaucracy and plain stupidness. There’s always someone who is against you and against what you are doing.”

Has you felt like giving up?” I ask.

“Oh yes. Many times. But every time something goes wrong, every time, you can’t just think it’s over. This is my third re-build of the whole operation. You couldn’t bloody write it. When it comes to dreams, there are a lot of people out there who don’t pursue them either because they don’t think they can achieve it or they think that other people will think they’re daft. Ultimately, we’re all just afraid of rejection. You know, none of us have to do anything with our lives but I’ll carry on doing what I’m doing. I’ll only give up if it’s on my terms.”

One can only admire Neil’s tenacity. But what drew him to Scotland?

“Being content is one thing,” he says. ” But equally, I want to challenge myself. I have no feeling of competition or envy. There’s no one else I’d like to swap my life with. I hate to underperform and I get frustrated if I don’t perform to the standard I set myself. I also can’t just set out on a journey and do it haphazardly. Ultimately, I enjoy the simple things, they are what give me the greatest pleasure.”

We call it a night. After just one day up here I feel full of enthusiasm. I couldn’t wait for the morning to come.

Trout caught in the loch that day for dinner.

Neil Gregory (left) and David Blundell, our photographer (right) at dinner.

My bed for the night in the Lochearnhead Hotel.

View from my hotel room window – it looks right out over the loch from which you fly from.

DAY TWO

There’s a roaring log fire burning away in the cafe. That’s summer in Scotland for you. Neil is sat in front of it, opening his mail and eating black pudding in a bap for breakfast. We’re in for a day of sitting around because the cloud is low on the hills, really low, and the water surface is rough. Time spent sitting around isn’t wasted though. I find my conversations with Neil flutter between adventure, flying and weird things that have happened to us in the past. With tea on tap (because Neil owns the cafe) there was one particular seating area we kept getting drawn to, and that was the chairs next to the aviation chart on the wall. Neil has stuck a red pin on each loch or stretch of water where he has landed G-WATR. Some of the locations are staggeringly remote. He reminds me that out of the 60 million people living in Great Britain, 80% of them are all south of us. Out of the remaining 20%, 80% of those are in the big cities, meaning that rural Scotland is pretty much close to being uninhabited.

“I have this image in my head of this little red aeroplane flying over this ancient land whenever I get airborne,” he says as we look at the chart. “In the summer, the landscape is soft and verdant, with the bees lazily buzzing yet only minutes away by plane you can be in a totally alien landscape with remnants of snow still on the peaks.”

When Neil talks like this it makes me wish I was up living here, doing what he does. Neil regaled so many of his personal flying stories throughout the day. I’d love to write about them now, but they are so incredible they’re best left for him to tell you himself.

He might have made home here, but it’s clear that Neil is well aware there is a big world out side of Loch Earn. In the past he has lived in some of the poorest places in the world. He tells me you’d think the spirit of the people living there would be broken, but they’re not. In his eyes, the people working in offices in cities and then sitting in traffic jams to go home to plasma TV screens are the ones with broken spirits.

LEARN HOW TO FLY A SEAPLANE

Neil has been responsible for creating and nurturing more seaplane pilots than any other instructor or examiner in the UK. At one point he was the only pilot flying a seaplane here in the UK. I meet one of Neil’s success stories later that night in the hotel bar. Neil Heron is a 29-year-old who now flies for Loch Lomond seaplanes flying a Cessna Turbo Stationair T206H on floats.

“Neil Heron came to me already having completed his ATPL exams, telling me he wanted to fly seaplanes commercially. As soon as I flew with him I could tell he had a good pair of hands. Being a natural pilot is a huge advantage but he has worked his way up through the ranks and has been bloody determined.”

Neil Heron says the seed was planted when he saw a seaplane in Australia and got talking to the pilot about it. The journey to get from there to where he is now has talken six years of long, hard graft.

“Flying a seaplane is very much a thinking man’s game,” he tells me. “I just love that you aren’t on an airport and you can park and take off from pretty much where you want. When I was doing my training with Neil, we parked on a sandy beach, had a cup of tea and then when it came time to go, he said, ‘Right, so how are we going to get out of here then?’. He left it all to me to decide. You have to think your way back out across the water. There are no taxiways, windsocks or Air Traffic Control to help you.”

Day Three of flying.

Having these two seaplane pilots sitting next to each other now really starts to bring out the intricacies of operating on floats. The instructor and former student, now professional, feed off each other.

“It’s just proper seat of the pants flying,” Neil Heron exclaims. “I’ve done some taildragger flying and that made a massive difference to my seaplane flying. The seaplane course was just the whole stimulation of not having a runway or any ground limitations. It’s really taught me about what flying really is. You have to think all the time and it keeps the mind busy. Jet skiers get in the way for example on Loch Lomond, some have even tried to race me when I take off! Then when it comes to taxiing, it’s amazing how you can move yourself around. You really have to pick your route through the boats carefully.”

Neil Gregory jumps in and explains that although you might pass the rating and add a seaplane SEP to your licence, it doesn’t mean you’re necessarily ready to fly solo.

“The course is about gaining the tools but then you have to use those tools to understand a bit more about how to fly a seaplane. Sometimes it may be you have to use two of those tools crossed at 90° to deal with a situation on the water that you’ve not seen before. There’s no ATC to make some of the decisions for you.”

Neil has flown professionally for a while now and says that to be a good seaplane pilot in these parts you need to be good at mountain flying, good at reading the weather and good at making the right call on when not to fly. “A lot of it is about confidence. My first ever docking was more scary than my first solo in a landplane. But you have to grab the bull by the horns in this game. Things can unravel real fast in a seaplane. Water is hard stuff.”

DIPPING YOUR TOES IN

I didn’t get to fly with Neil a second time because of the weather. Needless to say, after three days of Neil’s storytelling, my imagination has been completely captured. I feel like I’ve found the type of flying that suits me. I most certainly know Neil has. I sense that although he’s found happiness here, there’s a calling for him elsewhere.

“I’m at a point now where I know how to do this,” he says as I load up the boot of my hire car to drive back to Glasgow airport. “I want to give something back. My dream would be to do some relief flying, like delivering a cold box of vaccine in the jungle and landing on the Amazon river. I’m really interested in the third world and the aid agencies. What I can bring to the party is my seaplane, the skills to operate it and my time because I don’t have any ties here. I really think seaplanes will totally explode again in terms of their use.”

Typically the sun comes out on the day I leave.

Last I heard, Neil was flying G-WATR across Europe to fly ski-planes in Switzerland. He even flew it past the Matterhorn. I have no idea if he’ll leave Loch Earn, but you can sure bet that if there’s water somewhere, Neil will be there with his seaplane.

There’s dipping your toe in to try something new and then there’s completely getting your feet wet. After just three days at Neil’s Seaplanes, I know what my approach is going to be.

COMMENTS